The Research Partnership for Professional Learning (RPPL) and RPPL’s research team developed and designed the following toolkit to help educators, professional learning (PL) providers, and district leaders measure and monitor the implementation of high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) and curriculum-based professional learning (CBPL).

Across the country, school districts are betting that teachers’ use of high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) will profoundly improve student achievement1, particularly when teachers are supported by professional learning (PL) grounded in the curriculum.2

How will we know whether these efforts are working? Rigorous studies have confirmed that HQIM can produce large and positive effects on student learning.3 But curricular shifts are notoriously difficult to track.4 This is in part because the field lacks common measurement instruments that are practical and easy to use, leaving states, districts, and PL providers to develop custom tools to gather data on their HQIM and curriculum-based PL (CBPL) efforts.5 We are therefore short on broader insights into where and under what conditions the promise of HQIM and CBPL is being realized.

This updated toolkit provides a set of shared instruments to measure critical aspects of curriculum implementation in English Language Arts (ELA) and Mathematics across grades 3-12. The toolkit’s surveys and classroom observation protocols are designed to help PL providers, district leaders, coaches, and others ask and answer questions about HQIM and CBPL implementation and outcomes. The tools can be tailored by subject area (ELA or Math) and used to gather data for continuous improvement, planning, and resource allocation.

The instruments and Shared Measures Construct Map (below) were compiled and reviewed by the Research Partnership for Professional Learning (RPPL) in concert with PL providers and researchers.

What’s new in this version? The toolkit is an update to a previous version focused only on curricular shifts in ELA. The survey instruments include both a subject-agnostic version and versions specific to either ELA or Math.

The update also has a sharpened scope and includes revisions to our original ELA measurement system based on learnings from a pilot conducted with PL providers within RPPL’s network and the districts in which they provide PL. In particular, the updated toolkit includes more opportunities to triangulate patterns across data sources and offers multiple instrument configurations for different use-cases.

This toolkit supports PL providers, district leaders, and coaches who want to track implementation progress and PL quality across the first several years of ELA and/or Math curriculum shifts. The measures included in the toolkit can be used to:

- understand the state of CBPL and HQIM implementation across the system

- support improvement efforts, tracing links in a theory of change and surfacing points of breakdown

Users can implement the toolkit as a comprehensive suite of four instruments or select individual instruments, or dimensions within instruments, that are most relevant to their specific context and needs.

Importantly, the instruments in this toolkit are not designed for evaluating individual students, teachers, or schools.

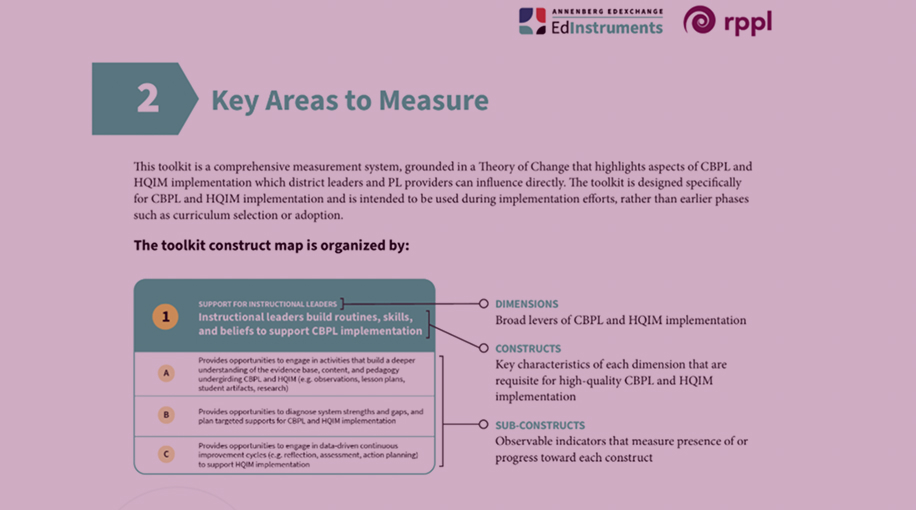

Key Areas to Measure

This toolkit is a comprehensive measurement system, grounded in a Theory of Change that highlights aspects of CBPL and HQIM implementation which district leaders and PL providers can influence directly. The toolkit is designed specifically for CBPL and HQIM implementation and is intended to be used during implementation efforts, rather than earlier phases such as curriculum selection or adoption.

The toolkit construct map is organized by:

- Dimensions. Broad levers of CBPL and HQIM implementation

- Constructs. Key characteristics of each dimension that are requisite for high-quality CBPL and HQIM implementation

- Sub-constructs. Observable indicators that measure presence of or progress toward each construct

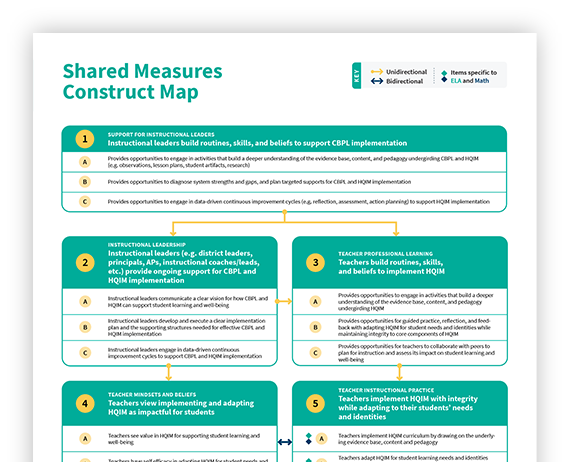

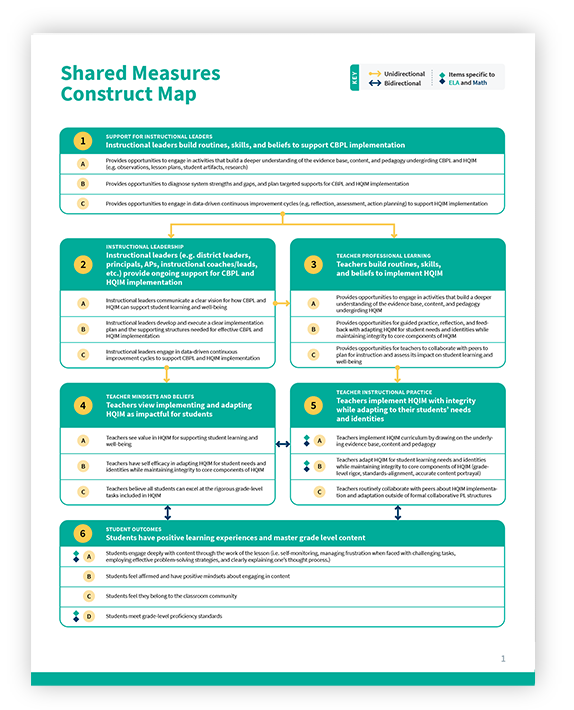

SUPPORT FOR INSTRUCTIONAL LEADERS

Instructional leaders build beliefs, routines, and skills, to support CBPL implementation

We focus on supports that are fundamental to CBPL and HQIM implementation for leaders – deepening their understanding of the evidence base for CBPL and HQIM, diagnosing system strengths and gaps to inform planning, and leading data-driven continuous improvement cycles to strengthen implementation.6

INSTRUCTIONAL LEADERSHIP

Instructional leaders (e.g. district leaders, principals, APs, instructional coaches/leads, etc.) provide ongoing support for CBPL and HQIM implementation

Leading effective HQIM implementation requires a vision for how CBPL and HQIM can support student learning along with the ability to communicate, execute, and continuously improve upon that vision.7

TEACHER PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

Teachers build routines, skills, and beliefs to implement HQIM

Evidence suggests that key elements of PL—deepening content and pedagogical understanding, guided practice, opportunities for reflection, targeted feedback, and collaboration—help teachers implement new instructional practices and curriculum materials with confidence.8

Teacher Mindsets and Beliefs

Teachers view implementing and adapting HQIM as impactful for students

Teachers’ beliefs and mindsets are one mechanism through which curricular shifts can lead to improved student learning. This includes teachers’ belief that HQIM are a critical tool to provide all students with rigorous, grade-appropriate content and the belief that all students can excel without diluting the rigor of content.9 Evidence suggests these beliefs can translate into teacher behaviors or expectations that in turn make HQIM success more likely.10

TEACHER INSTRUCTIONAL PRACTICE

Teachers implement HQIM with integrity while adapting to their students’ needs and identities

We focus on how teachers take up, interpret, and enact the core components of HQIM – like grade-level rigor – while potentially adapting other components of the curriculum to accommodate their students or contexts. Implementing with fidelity a curriculum’s central principles is associated with successful outcomes, but “productive adaptations” of some program aspects can also enhance student learning gains.11

STUDENT OUTCOMES

Students have positive learning experiences and master grade level content

Students learn best in an environment where they feel that their identities are respected and affirmed12 and when they are challenged with rigorous, grade-appropriate texts, questions, and tasks.13 To capture this, we include social-emotional outcome measures like belonging and affirmation as well as academic measures to ensure both academic and personal growth are measured as part of HQIM implementation.

Toolkit Development

This toolkit represents consensus recommendations developed by the Research Partnership for Professional Learning (RPPL) working with a set of key organizations all focused on building the conditions for more effective curriculum-based PL.

Toolkit Development Process

The instruments in this toolkit are the result of a two-year consensus process that balanced academic rigor with practical feasibility.

The instruments in this toolkit are the result of a two-year consensus process that balanced academic rigor with practical feasibility.

Working group members identified a series of shared constructs and sub-constructs that each organization considered central to its theory of action about how high-quality instructional materials and curriculum-based PL could improve classroom outcomes.

The group conducted a review of instruments used in research and practice that measured the shared constructs. This culminated in a comprehensive literature review that identified over 4,000 articles, reports, and briefs, which were narrowed to more than 500 sources for a close reading.

Research leads in the working group conducted an initial screening for relevance, quality, and feasibility. Then they created a shortlist of 4-8 tools per sub-construct, attending especially to content alignment, psychometric evidence, and usability in practice.

Working group participants individually reviewed each instrument shortlisted for each sub-construct, assessing strengths and limitations, including psychometric rigor and ease of administration. Then, the group collaboratively built recommendations from the short-listed options, selecting tools that would effectively meet measurement needs while maintaining a manageable number of items that could be used across different contexts and respondents.

Organizations piloted a subset of instruments and items with district partners to test feasibility and relevance in practice. The insights from the pilot and feedback from working group members led RPPL to refine and adapt the instruments into a common measurement system that could be implemented across subject areas.

Tailoring the Toolkit to Your Needs

This toolkit is designed to be flexible, allowing PL providers, district leaders, and coaches to choose the components that best fit their goals and context. For example, for those interested in understanding the state of CBPL and HQIM implementation across the system, the toolkit can help ask and answer questions like:

- What is the current status of CBPL and HQIM implementation overall?

- How does CBPL and HQIM implementation vary across the system?

- How has CBPL and HQIM implementation changed over time?

- How does CBPL and HQIM implementation in my context compare with other contexts (benchmarking)?

And for those interested in using the toolkit for continuous improvement efforts, such as tracing links in a theory of change and surfacing points of breakdown, the toolkit can help users ask and answer questions like: How do perceptions differ across stakeholder groups (triangulating viewpoints)?

- What drives variation in implementation and outcomes across the system?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the system?

- To what extent do the causal links in a theory of change show up in the data?

- To what extent is the system improving over time?

Consider the recommendations and information below, and download the Excel companion spreadsheet to filter the toolkit by your core purpose.

- Avoid picking single measures ad hoc. Begin with a clear purpose and think about how you’ll integrate chosen measures into your existing instruments or routines.

- Consider what data will be most valuable for your partners and for your own continuous improvement and progress monitoring purposes.

- Use multiple tools for the same sub-construct when you want to triangulate across respondents, gain a deeper understanding of your implementation or aren’t sure which data source will work best in your context.

Instrument Overview

Leader Survey

Recommendations:

- Minimum 70%-80% response rateD

Additional Considerations for Exploring Change Over Time:

For an apples-to-apples comparison, the same leaders (respondents) should be members of the sample at each occasion of measurement

A survey administered to district leaders, school leaders, coaches, and PL facilitators to understand:

- perceptions of supports received

- vision and approach to implementing HQIM

- the nature of teachers’ PL experiences

Teacher Survey

Recommendations:

- Minimum 70%-80% response rate

Additional Considerations for Exploring Change Over Time:

For an apples-to-apples comparison, the same teachers (respondents) should be members of the sample at each occasion of measurement

A survey administered to teachers to understand:

- the nature of the PL they participated in

- their perceptions of the utility of the PL they participated in

- their perceptions of their instructional leadership

Classroom Observation Protocol

Recommendations:

- Provide observers with training. For example, observers should practice rating teacher instructional practices together to norm their ratings prior to the start of observation for data collection. This will increase the likelihood of fair and reliable ratings

- Randomly select classrooms for observation to ensure a representative sample, in the event not all teachers can be observed

- Observe each classroom on two different occasions, using two different observers, to help reduce the impact of possible rater bias. These two ratings comprise one observation cycle; multiple cycles enable the measurement of change over time

- Avoid observing at times that are not representative of typical instruction, for example, close to school holidays or state testing windows

Additional Considerations for Exploring Change Over Time:

For an apples-to-apples comparison, the same sample of teachers should be observed from one observation cycle to the next

Estimating change over time can be particularly complex for classroom observation data - the more observation timepoints the better, particularly if there is a desire to explore variation in growth over time20

An observation rubric completed by a classroom observer (e.g. a coach or school leader) to understand how teachers are implementing and adapting HQIM and how students are engaging with ELA/Math content

Student Survey

Recommendations:

Minimum 70% - 80% response rate

Additional Considerations for Exploring Change Over Time:

For an apples-to-apples comparison, the same students (respondents) should be members of the sample at each occasion of measurement

A survey administered to the students of teachers that participate in PL to understand students’ sense of belonging and engagement with ELA/Math content

Classroom Observation Protocols and Training

The toolkit’s teacher instructional practice dimension is measured in part through classroom observations, which can provide important information about how teachers implement HQIM and enact what they learned in CBPL. The toolkit includes a Classroom Observation Protocol to collect data, with one version each for ELA and Math. The toolkit’s protocol combines elements from three published observation rubrics (see table below for sources) that were all designed to gather evidence on instructional quality. RPPL recommends that teams using this toolkit’s Classroom Observation Protocols engage in the following best practices and training to ensure that raters use the protocols in fair and reliable ways. Reliability in this context refers to both a single rater’s consistent rating over time as well as agreement between two or more different raters who observe and score the same classroom.

Best practices. An observation instrument articulates criteria for instructional quality, and observers look for evidence those criteria are met and score the evidence at some level of performance. To ensure that ratings are reliable across observation instances and across the different people conducting observations, teams should take the time to provide training on the classroom observation protocol. Training should include opportunities for multiple observers to rate the same educator (or video of educator performance) and debrief to make meaning of the evidence together, norm ratings, and ensure agreement.

Formal training. The following table lists the existing observation rubrics that were sampled, combined, and adapted for the Classroom Observation Protocols in this toolkit. Links to the source rubrics’ formal training and certification process are included. Completing the relevant training and certification prior to conducting observations is a critical step to ensure your team collects high-quality and consistent observation data.

DThese minimum response rate recommendations are based on empirical research and professional guidelines for the response rates likely to improve study designs and reduce bias in conclusions drawn from survey data, particularly when data are collected from a relatively small number of respondents. Bias refers to a situation in which the share of teachers, leaders, or students who respond to a survey do not represent (generalize to) all of the teachers, leaders, or students they represent, which can result in misleading conclusions. The recommended response rate is a range because the rate that produces data representative of an entire target audience - whether teachers, leaders, or students - will differ from one context to the next. See American Association for Public Opinion Research. (2022). AAPOR Standards best practices; Groves, R. M., Fowler Jr., F. J., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2009). Survey Methodology (2nd ed.). Wiley; Office of Management and Budget. (2006). Standards and guidelines for statistical surveys; Saldivar, M. G. (2012). A primer on survey response rates [White Paper]; Tipton, E., & Olsen, R. B. (2018). A review of statistical methods for generalizing from evaluations of educational interventions. Educational Researcher, 47(8), 516–524; Tipton, E., Hallberg, K., Hedges, L. V., & Chan, W. (2017). Implications of Small Samples for Generalization: Adjustments and Rules of Thumb. Evaluation Review, 41(5), 472–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X16655665.

Recommendations for Use

This toolkit is designed to help organizations and districts collect useful, timely, and consistent information about professional learning. The surveys and classroom observation protocol were designed to be flexible and modular because practitioners engaging in measurement activities face different constraints than researchers. However, this flexibility introduces a challenge. Decisions made for pragmatic reasons – such as which survey components a district should administer, or how many teachers a PL organization should survey or observe and on what timeline – can have consequences for the claims that the district or organization wants to make about CBPL and HQIM.

There are no hard and fast rules or magic thresholds for optimal data collection. Instead, decisions about how to collect data should be context-dependent and grounded in the specific questions that a practitioner or researcher wants to ask or inferences they wish to draw. For example, there are different considerations if data will be used to assess:

- the status or quality of CBPL and HQIM implementation at a specific point in time

- how CBPL and HQIM implementation vary across the system

- how implementation has changed over time

- how CBPL and HQIM implementation compares between two or more sites or organizations (benchmarking)

Below are high-level guidelines that balance research standards with practical constraints. The goal is to help PL providers, district leaders, and coaches make informed decisions about how to collect data and implement the instruments in this toolkit. We focus our guidelines on understanding the status of CBPL and HQIM implementation at a single point in time and include minimal comments on other use cases.

Data Collection Principles

This toolkit supports professional learning providers, district leaders, and coaches who wish to understand the state of CBPL and HQIM implementation across the system and support continuous improvement. The instruments in this toolkit are not designed for evaluating individual students, teachers, or schools.

Users are encouraged to consider the following principles:

- Representativeness matters: If you seek to understand practice across a district, conducting 20 observations in classrooms that represent the entire district is better than conducting 30 observations among the highest-performing teachers who volunteer to be observed.

-

More is always better:

- A 90% response rate allows more confidence in the conclusions drawn from the data than a 70% response rate.

- The use of more than one instrument in the toolkit – and triangulating data collected from different audiences, such as leaders and teachers, or teachers and students – will generally increase the credibility of conclusions, over and above the conclusions drawn from a single instrument. Using more than one method to collect data can also give important nuance to the conclusions. For example, where surveys can be widely administered to understand what teachers believe in theory, observations can be used to deeply understand how teachers enact those beliefs in practice, providing a more complete picture of curriculum implementation.18

- Change over time requires higher-quality data collection: Additional considerations appear in the guidelines below for data collected on more than one occasion with the intent to explore change over time. The higher standard for data collected at two or more time points helps ensure that differences observed over time reflect true change rather than measurement error or shifts in the sample.

Data Collection Calendar

Choose the data collection calendar based on the frequency your team has the capacity to manage. We recommend starting with fewer touchpoints and building up over time as systems strengthen.

- Annual: One point of data collection, ideally in early spring, to capture perceptions before the end of year.

- Bi-annual: Two touchpoints, in fall and spring, to provide a beginning- and end-of-year perspective.

- Three times per year: Early fall, winter, and spring, allowing for closer monitoring of curriculum implementation.

SAMPLE CALENDAR

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

What to administer:

- Student Survey

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

- Student Survey

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

- Student Survey

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

- Student Survey

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

- Student Survey

What to administer:

- Leader Survey

- Teacher Survey

- Classroom Observations

- Student Survey

Preliminary Insights from Year 1 Pilot

In Spring 2025, several PL providers within the RPPL network partnered with districts to pilot a subset of the measurement toolkit focused on ELA curriculum implementation. The shared measures pilot informed key updates to the toolkit, which included:

Subject-agnostic Framework

Shifting from an ELA-specific toolkit to a subject-agnostic framework with ELA- and Math-specific measures, enabling use across content areas for PL providers and district leaders alike.

Theory of Action

Restructuring the measurement toolkit as a Theory of Action that highlights the key levers district leaders and PL providers can use to improve HQIM implementation and related student outcomes. This included replacing the School & System Conditions dimension with the Support for Instructional Leaders dimension as a key lever for driving the Instructional Leadership dimension.

Combining Sub-constructs

Combining academic and social-emotional learning sub-constructs into a single student outcomes dimension, reflecting the many connections and feedback loops between these outcomes.

Criteria Clarification

Refining the criteria for what’s included in the toolkit to focus on constructs and measures directly related to HQIM implementation, rather than those that measure high-quality leadership, professional learning, or instruction in general. We also prioritized measures that apply across all stages of HQIM implementation post adoption.

Teacher Collaboration

Adding teacher collaboration as a key feature of CBPL and a key driver of high-quality implementation of HQIM for all students, in alignment with RPPL’s publication Defining Curriculum-Based Professional Learning: Building a Common Language, and feedback received on the original toolkit.

Data Triangulation

Adding opportunities to triangulate data across sources and clear pathways for tailoring the toolkit for different uses and audiences.

Through our Data and Infrastructure initiative, RPPL analyzed and visualized the Year 1 shared measures data of the PL providers participating in the pilot. These analyses provided a deeper view of each PL organization’s CBPL efforts supporting curriculum shifts in various district contexts and offered shared benchmarks to surface strengths and opportunities to refine their PL design.

In Year 2, RPPL partners will continue piloting the ELA shared measures with a focus on four key learning questions:

- What about PL design has to be happening to drive instructional improvement?

- What aspects of PL design drive instructional improvement?

- How does train-the-trainer compare to direct-to-teacher PL (e.g., scale vs. quality)?

- What supports should PL providers prioritize for supporting HQIM implementation in ELA?

By measuring similar outcomes using the same instruments and approaches, the pilot will generate shared learning for the RPPL partners and the field about supporting HQIM implementation through PL.

Implementation Snapshots

The Professional Learning Network in RI (PL Network) is a partnership between the Rhode Island School Superintendents Association and the Annenberg Institute that brings together Rhode Island districts to collaborate and learn from one another on improving classroom instruction and student outcomes through CBPL. The PL Network uses shared measures to monitor district progress, guide continuous improvement, and strengthen collective learning.

In Year 1, the PL Network initially relied upon the existing measurement tools in each of the six districts to track progress, but the approach proved time-consuming and difficult to sustain. When the ELA Measurement Toolkit was released, the network pivoted and piloted the student, teacher, and leader surveys as a one-time pulse check to learn:

- how students were experiencing curriculum and instruction,

- how teachers were experiencing professional learning, and

- how leaders perceived PL and curriculum shifts.

Partner districts found the data compelling, with several incorporating them into school board presentations and planning processes for the next school year. For example, in one district the student survey showed that students did not feel like they were "thinking hard" in class. At the same time, teachers said they both did not have access to the materials necessary to implement their curriculum and that their professional learning did not equip them to help deepen students' understanding of the content. The aligned teacher and student surveys helped the district identify teacher support for deeper high-quality curriculum implementation as a next step for their professional learning strategy.

Building on learnings from Year 1, the network is narrowing its focus in Year 2 to elementary and middle grade math, aiming to deepen students' cognitive engagement and strengthen readiness for Algebra I by the end of 9th grade. In line with these new learning goals, the network selected a subset of math-specific items from the updated toolkit to serve as a shared measurement system across the PL Network. Surveys will be administered three times a year and embedded into existing district data routines to reduce burden on staff. Year 2 data will inform deep dive visits to each district, where network-wide trends will be shared for collective learning and district-specific findings will support joint meaning-making and progress monitoring against each district's goals.

The measurement toolkit has been designed for the very purpose of being nimble and adaptable across contexts and evolving priorities. For the PL Network, that meant using it in Year 1 as a one-time pulse check and then adapting it to a narrower math focus in Year 2.

As one of RPPL's partners piloting the ELA shared measures in Spring 2025, Instruction Partners (IP) set out to test the toolkit and help inform this update. IP integrated the teacher and leader survey items into its existing instruments. Incorporating the instruments from the toolkit helped deepen data collection and strengthen conversations with district partners about conditions for effective PL and curriculum implementation.

Using Year 1 data from the survey items, along with additional qualitative data from focus groups, interviews, and artifacts, IP produced diagnostic reports for its school and district partners. These reports summarized strengths and opportunities for improvement across the IP's Enabling Conditions framework. Findings were shared at summer leadership summits and used to guide district leaders' planning for the new school year. Importantly, because the survey items are now common measures across partners, IP can not only provide districts with consistent, comparable yearly data but also benchmark implementation across partners to drive continuous improvement.

IP plans to continue to embed the toolkit items into its existing instruments, collecting data to support diagnostic reporting for its district partners while contributing to the Year 2 ELA shared measures pilot as well.

Notes

- Council of Chief State School Officers. (2021). How states can support the adoption and effective use of high-quality standards aligned instructional materials. CCSSO High Quality Instructional Materials & Professional Development Network; Council of Chief State School Officers. (2024). Impact of the CCSSO IMPD Network. CCSSO High Quality Instructional Materials & Professional Development Network; Doan, S., Kaufman, J. H., Woo, A., Prado Tuma, A., Diliberti, M. K., & Lee, S. (2022). How states are creating conditions for use of high-quality instructional materials in K–12 classrooms: Findings from the 2021 American Instructional Resources Survey. RAND Corporation; EdReports & Decision Lab. (2025). Beyond selection: Rethinking how districts adopt curriculum; Opfer, V. D., Kaufman, J. H., & Thompson, L. E. (2017). Implementation of K–12 state standards for mathematics and English Language Arts and literacy: Findings from the American Teacher Panel. RAND Corporation; Partelow, L., & Shapiro, S. (2018). Curriculum reform in the nation's largest school districts. Center for American Progress; Steiner, D. (2024). The unrealized promise of high-quality instructional materials. State Education Standard: The Journal of the National Association of State Boards of Education, 24(1).

- CCSSO (2024); Chu, E. C., McCarty, G. M., Gurny, M. G., & Madhani, N. M. (2022). Curriculum-based professional learning: The state of the field. Center for Public Research & Leadership; Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute; EdReports & Decision Lab (2025); Steiner, D. (2017). Curriculum research: What we know and where we need to go. StandardsWork.

- Agodini, R., Harris, B., Atkiins-Burnett, S., Heaviside, S., Novak, T., & Murphy, R. (2009). Achievement effects of four early elementary school math curricula: Findings from first graders in 39 schools (NCEE 2009-4052). Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Blazar, D., Heller, B., Kane, T. J., Polikoff, M., Staiger, D. O., Carrell, S., Goldhaber, D., Harris, D. N., Hitch, R., Holden, K. L., & Kurlaender, M. (2019). Learning by the book: Comparing math achievement growth by textbook in six Common Core states. [Research Report]. Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University; Boser, U., Chingos, M., & Straus, C. (2015). The hidden value of curriculum reform: Do states and districts receive the most bang for their curriculum buck?. Center for American Progress; Chingos, M. M., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2012). Choosing blindly: Instructional materials, teacher effectiveness, and the Common Core. Brookings Institution; Gallagher, H. A. (2021). Professional development to support instructional improvement: Lessons from research. SRI International; Lynch, K., Hill, H. C., Gonzalez, K. E., & Pollard, C. (2019). Strengthening the research base that informs STEM instructional improvement efforts: A meta-analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(3), 260–293.; Novicoff, S. & Dee, T.S. (2025). The achievement effects of scaling early literacy reforms (EdWorking Paper No. 23–887). Annenberg Institute at Brown University; Steiner (2017).

- Alicea, S., Davis, C., Foster, E., Hornak, R., Hyler, M., Morrison, A., Papay, J., Richardson, J., Schwartz, N., & Wechsler, M. (2025). Defining curriculum-based professional learning: Building a common language. Research Partnership for Professional Learning, Annenberg Institute at Brown University; Chingos & Whitehurst (2012); Partelow & Shapiro (2018); Polikoff, M. (2018). The challenges of curriculum materials as a reform lever (No. Vol. 2, #58; Evidence Speaks Reports). Brookings Institution; Steiner (2017).

- Alicea, S., Buckley, K., Cordova-Cobo, D., Husain, A., Meili, L., Merrill, L., Morales, K., Schmitt, L., Schwartz, N., Tasker, T., Thames, V., & Worthman, S. (2023). Measuring teacher professional learning: Why it's hard and what we can do about it. Research Partnership for Professional Learning.

- Ward, C., Nacik, E., Perkins, Y., & Kennedy, S. (2024). Effective implementation of high-quality math curriculum and instruction. FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina; EdReports & Decision Lab (2025).

- Miller, A. F., & Partelow, L. (2019). Successful implementation of high-quality instructional materials. Center for American Progress; National Comprehensive Center. (2023). Guide to the implementation of high-quality instructional materials (HQIM). Comprehensive Center Network and Accelerate Learning; Short, J., & Hirsh, S. (2020). The elements: Transforming teaching through curriculum-based professional learning. Carnegie Corporation of New York; Steiner (2024).

- Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers' professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199; Hill, H. C., Beisiegel, M., & Jacob, R. (2013). Professional development research: Consensus, crossroads, and challenges. Educational Researcher, 42(9), 476–487; Hill, H. C., Papay, J. P., & Schwartz, N. (2022). Dispelling the Myths: What the Research Says about Teacher Professional Learning. Research Partnership for Professional Learning, Annenberg Institute at Brown University; Hill, H. C., & Papay, J. P. (2022). Building better PL: How to strengthen teacher learning. Research Partnership for Professional Learning, Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

- Doan, S., & Shapiro, A. (2023). Do teachers think their curriculum materials are appropriately challenging for their students? Findings from the 2023 American Instructional Resources Survey. RAND Corporation; Eells, R. (2011). Meta-Analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement [Dissertation, Loyola University Chicago]; TNTP. (2024). The Opportunity Makers—How a diverse group of public schools helps students catch up—and how far more can; Wolf, S., & Brown, A. (2023). Teacher beliefs and student learning. Human Development, 67(1), 37–54; Yeager, D. S., Carroll, J. M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., Kersting, N., Hulleman, C., Kudym, M., Murphy, M., Duckworth, A. L., Walton, G. M., & Dweck, C. S. (2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn't work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18–32.

- Wolf & Brown (2023); Yaeger et al. (2022)

- Hill et al. (2022); Hill, H. C., & Erickson, A. (2019). Using implementation fidelity to aid in interpreting program impacts: A brief review. Educational Researcher, 48(9), 590–598; Kim, J. S. (2019). Making every study count: Learning from replication failure to improve intervention research. Educational Researcher, 48(9), 599–607; Kim, J. S., Burkhauser, M. A., Quinn, D. M., Guryan, J., Kingston, H. C., & Aleman, K. (2017). Effectiveness of structured teacher adaptations to an evidence-based summer literacy program. Reading Research Quarterly, 52(4), 443–467; McLaughlin, M. W., & Mitra, D. (2001). Theory-based change and change-based theory: Going deeper, going broader. Journal of Educational Change, 2(4), 301–323; McMaster, K. L., Jung, P.-G., Brandes, D., Pinto, V., Fuchs, D., Kearns, D., Lemons, C., Sáenz, L., & Yen, L. (2014). Customizing a research-based reading practice. The Reading Teacher, 68(3), 173–183; Steiner (2017).

- Healey, K., & Stroman, C. (2021). Structures for belonging: A synthesis of research on belonging-supportive learning environments. Student Experience Research Network; Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L., & Krone, C. R. (2019). Nurturing nature: How brain development is inherently social and emotional, and what this means for education. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 185–204.

- ACT. (2006). Reading between the lines: What the ACT reveals about college readiness in reading. ACT, Inc; Center for Public Education. (2025). Defining high-quality instructional materials for math: A school board priority. National School Boards Association; Shanahan, T. (2025). Leveled Reading, Leveled Lives: How Students' Reading Achievement Has Been Held Back and What We Can Do About It. Harvard Education Press; Steiner (2024).

- Danielson, C. (2012). Observing classroom practice. Educational Leadership, 70(3), 32-37; Marshall, K. (2013). Rethinking teacher supervision and evaluation: How to work smart, build collaboration, and close the achievement gap, 2nd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Desimone, L., Litke, E., & Snipes, J. (2025). Chapter 14: Considerations in using classroom observations to measure the effects of professional learning. In: S. Kelly (Ed.), Research Handbook on Classroom Observation.

- Boguslav, A., & Cohen, J. (2023). Different Methods for Assessing Preservice Teachers' Instruction: Why Measures Matter. Journal of Teacher Education, 75(2), 168-185; Briggs, D. C., & Alzen, J. L. (2019). Making Inferences About Teacher Observation Scores Over Time. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(4), 636-664

Sources (instruments and items)

Center for the Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning. (2023). Tools for equitable reading instruction. University of Virginia. https://instructionaltools.org/

Cribbs, J., & Utley, J. (2023). Mathematics identity instrument development for fifth through twelfth grade students. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-023-00474-w

Doan, S., Eagan, J., Grant, D., & Kaufman, J. H. (2024). American Instructional Resources Surveys: 2024 technical documentation and survey results (RR-A134-24). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-24.htm

Gates Foundation. (2024) K-12 Enactment Survey

Gehlbach, H., & Harvard Graduate School of Education. (2014, August). Panorama student survey. Panorama Education. https://www.panoramaed.com/products/surveys/student-survey

Hill, H. C. (n.d.). Mathematical Quality of Instruction (MQI) rubric. Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University. https://mqicoaching.cepr.harvard.edu/rubric

Illustrative Mathematics. (2024, November). IMplementation reflection tool: Grades K–12. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xXYmH-U1TZPa28UCOhNXxPMIdGTRM2cs/view

Instruction Partners. (n.d.). Collaborative planning: Facilitator survey. https://instructionpartners.org

Johnson, N. C., Franke, M. L., & Turrou, A. C. (2022). Making competence explicit: Helping students take up opportunities to engage in math together. Teachers College Record, 124(11), 117–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221139532

Schweig, J., Pandey, R., Grant, D., Kaufman, J. H., Steiner, E. D., & Seaman, D. (2023). American Mathematics Educator Survey: 2023 technical documentation and survey results (RR-A2836-1). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2836-1.html

Smith, E. P., & Desimone, L. M. (2025). Coach and teacher alignment in the context of educational change. Journal of educational change, 26(2), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-025-09528-1

Soine, K. M., & Lumpe, A. (2014). Measuring characteristics of teacher professional development. Professional Development in Education, 18(3), 303–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2014.911775

Transcend Education. (2022). Leaps student voice survey. https://transcendeducation.org/leaps-student-voice-survey/

UnboundEd. (2025). Integrity Walk tool. https://unbounded.org